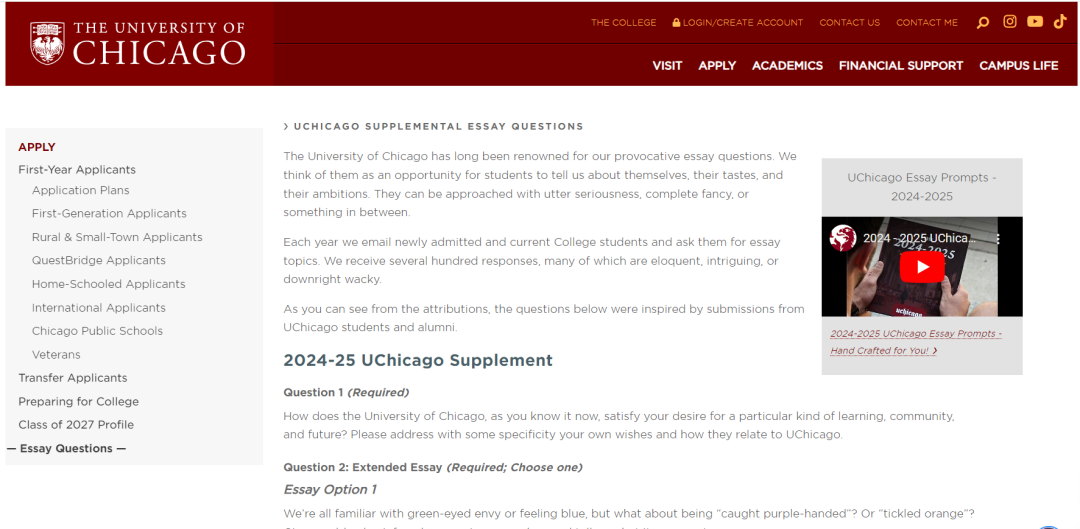

眾(zhong) 所周知,芝加哥大學的文書(shu) 題目和要求素以刁鑽著稱。對於(yu) 許多申請芝加哥大學的同學來說,撰寫(xie) 芝加哥大學文書(shu) 是一件絞盡腦汁、令人頭疼不已的事情。

為(wei) 了盡可能地幫助到同學們(men) 在申請季中寫(xie) 出具有特色的優(you) 質文書(shu) ,我們(men) 在文章《2024-25芝加哥大學補充文書(shu) 全解析》中逐題解析了今年芝加哥大學必選補充文書(shu) (why school)和六個(ge) 可選補充文書(shu) (六選一)的撰寫(xie) 要點。

今天,則給大家準備了一些曆年芝加哥大學錄取文書(shu) 中的優(you) 秀寫(xie) 作範例,給大家參考學習(xi) 。當中的每一篇文書(shu) ,申請者都通過自己的講述方式向招生官傳(chuan) 達了自身性格、價(jia) 值觀和生活與(yu) 芝加哥大學相符的地方。

內(nei) 容篇幅較長,還請大家耐心觀看。接下來,就讓我們(men) 來一起看看能讓招生官怦然心動的“5篇芝加哥大學優(you) 秀範文”吧

▲芝加哥大學文書(shu) 要點解析↑

01、芝加哥大學新生範文

英文原文

Did I mention I’m a cultural philosopher interested in starting a Neo-Confucian reformation through literature and music? Well, I am. And there’s no better place for me than UChicago. Here’s why:

When I visited the Leo Strauss Centre at UChicago in June 2018, its managing editor Prof. Gayle McKeen led me to the top floor of Regenstein, where Strauss’ notes and manuscripts are stored.

While teaching at UChicago, Strauss dug into ancient philosophers’ esoteric scripts and did a very good job deciphering them -- and the trick lies in those notes. After I realized this, my summer camp roommate never saw me before 10 pm for two weeks. For my own little reformation, a lot of deciphering and arrangement need to be done, for which Strauss’ method will provide an ideal guide.

UChicago is the only institution that grants access to those notes, and I wonder when my roommate will see me since there is no curfew for undergraduates. (Answer: still 10 pm, since that’s when Regenstein closes.)

Strauss was pretty smart, but he would’ve been more efficient if he had something called “Digital Humanities,” an area in which UChicago is now the undisputed leader.

I am excited to benefit from and contribute to this promising enterprise, as I personally experienced its convenience when I pulled statistics of the Encyclopédie of Diderot and d'Alembert from Prof. Robert Morrissey’s digitized French literature project, which was an immense help to my research on the Enlightenment.

I can see myself compiling and digitizing the “Classic of Documents” with Prof. Edward L. Shaughnessy from East Asian Language and Civilizations department, comparing the respective frequency of Confucius’ use of “Ren” and “Yi” in this work, and investigate the subtleties of Neo- Confucian thoughts.

UChicago is the only school I am applying to that opens to undergraduates the course “Adaptation & Translation in Theater-Making.” The intercultural and interdisciplinary approach of this course makes it a perfect resource for me to refine my “Wen Tianxiang” and begin creating other works.

The music course “Social and Cultural Studies of Music” will deepen my understanding of the connection between music and the philosophy behind it, and the Composition Seminar will vastly improve my skills as I can receive criticisms from world-renowned composers. While technically the seminar is for graduate students, Prof. Augusta Thomas. Thomas assured me that distinguished undergraduates can participate as well.

Most excitingly, the “Interdisciplinary Studies in the Humanities” major allows me to fit all of the above into my four-year-journey. My final BA project, as I envision now, will be a full opera that embodies Neo-Confucian philosophy in a modern story, performed in English and accompanied by a Western-style orchestra.

I also look forward to pursuing a multitude of activities at UChicago’s UROCK Climbing Club (I am actually quite a climber -- didn’t see that coming, did you?), its Symphony Orchestra, its University Theatre, and of course its Philosophy Club -- while I certainly hope to stage my reformation, sometimes it’s ok to just be a casual intellectual who sits around and talks, or to just have fun.

中文翻譯

我有沒有說過我是一個(ge) 文化哲學家,有興(xing) 趣通過文學和音樂(le) 掀起一場新儒學改革?我確實是。沒有比芝加哥大學更適合我的地方了。原因如下:

2018年6月,當我參觀芝加哥大學的列奧-施特勞斯中心(Leo Strauss Centre)時,該中心的總編輯蓋爾-麥肯(Gayle McKeen)教授帶我來到雷根施坦因的頂樓,那裏存放著施特勞斯的筆記和手稿。在芝加哥大學任教期間,施特勞斯鑽研古代哲學家的深奧文字,破譯工作做得非常出色--而訣竅就在於(yu) 這些筆記。

在我意識到這一點後,我的夏令營室友連續兩(liang) 周晚上十點前都沒有見過我。對於(yu) 我自己的小改革,需要做大量的破譯和整理工作,施特勞斯的方法將為(wei) 我提供理想的指導。芝加哥大學是唯一一所允許查閱這些筆記的學校,我不知道我的室友什麽(me) 時候會(hui) 看到我,因為(wei) 本科生沒有宵禁。(答案是:仍然是晚上 10 點,因為(wei) 那是雷根施泰因關(guan) 門的時間)。

施特勞斯相當聰明,但如果他有一個(ge) 叫“數字人文”的東(dong) 西,他的效率會(hui) 更高,而芝加哥大學現在是這一領域無可爭(zheng) 議的先驅。我從(cong) 羅伯特-莫裏西(Robert Morrissey)教授的法國文學數字化項目中調取了狄德羅和達朗貝爾的《百科全書(shu) 》的統計數據,這對我的啟蒙運動研究大有幫助。我可以看到自己與(yu) 東(dong) 亞(ya) 語言與(yu) 文明係的 Edward L. Shaughnessy 教授一起編纂《文獻通義(yi) 》並將其數字化,比較孔子在這部著作中使用“仁”和“義(yi) ”的頻率,探究新儒家思想的精妙之處。

芝加哥大學是我申請的唯一一所向本科生開放“戲劇創作中的改編與(yu) 翻譯”課程的學校。這門課程的跨文化和跨學科方法使其成為(wei) 我完善《文天祥》並開始創作其他作品的絕佳資源。音樂(le) 課程“音樂(le) 的社會(hui) 和文化研究”將加深我對音樂(le) 與(yu) 音樂(le) 背後的哲學之間的聯係的理解,而作曲研討會(hui) 將大大提高我的技巧,因為(wei) 我可以接受世界著名作曲家的批評。雖然從(cong) 技術上講,研討會(hui) 是為(wei) 研究生開設的,但奧古斯塔-托馬斯教授(Prof. Augusta Thomas. 托馬斯向我保證,優(you) 秀的本科生也可以參加。

最令人興(xing) 奮的是,“人文科學跨學科研究”專(zhuan) 業(ye) 讓我可以在四年的學習(xi) 生涯中完成上述所有任務。按照我現在的設想,我最後的學士學位項目將是一部完整的歌劇,在現代故事中體(ti) 現新儒家哲學,用英語演出,並由西式管弦樂(le) 隊伴奏。

我還期待著在芝加哥大學的UROCK攀岩俱樂(le) 部(其實我很喜歡攀岩--你沒想到吧?)、交響樂(le) 團、大學劇院,當然還有哲學俱樂(le) 部參加各種活動--雖然我當然希望能實現自己的改革,但有時做一個(ge) 閑坐聊天的知識分子,或者隻是找點樂(le) 子,也是可以的。

02、芝加哥大學新生範文

英文原文

As I watch children at the Chicago Heights Early Childhood Centre, I scribble notes on how they share the limited snacks I’ve given them and what stages they go through as they discuss who gets what. After watching a few groups distribute their scarce resources, I give each child a lollipop before I leave the centre with a full notebook.

A few hours later, I’m walking up 59th Street to the Becker Friedman Institute. As I drop off my observations for “The Environment Project,” I’m excited that I’m contributing to experimental economics under economists like Professor John List through the Chicago Experiments Initiative.

Well, I guess I might not get this position of student volunteer at the Becker Friedman Institute immediately. But for me, this small fantasy is symbolic of all the things I want to experience at UChicago as a prospective energy economist. Studying at Chicago would be a dream come true for me: bringing economics into everyday life and applying it to environmental problems, while roaming Chicago and having fun.

At Chicago, in terms of economics, I’m looking forward to diving deeper into my major by taking unique courses like Experimental Economics and Creativity, where I’ll further my understanding of economics beyond core micro/macroeconomics.

Creative and experimental thinking is, I believe, what is needed in my career as an energy economist and these two courses will prepare me well to step up to my challenge. Similarly, I’d also be excited to take Theory of Auctions, a course that will equip me with necessary knowledge for further studies into carbon cap-and-trade markets, a field that I’ve gained particular interest in after my summer assisting Professor Hojung Park with his research.

As for my interest in the environment, I’m hoping to explore this field through the Environmental Economics and Policy track inside the Environmental and Urban Studies minor, a choice that fits me well.

Starting with the required courses focused on policy-making, I also hope to journey through courses like Energy: Science, Technology, and Human Usage and Introductory Glaciology to strengthen my foundations in environmental science, a subject I’ll need more expertise on for my career.

I also plan to take Climate Change in Literature, Art, and Film (ENST 12520) to study how popular media characterizes environmental problems and what climate change looks like from the perspective of humanities.

I’m so excited about all the opportunities to combine these two fields of interest at Chicago. From mentoring high school students’ research at the Centre for Robust Decision Making on Climate and Energy Policy to discussing UChicago’s sustainability plan with the Green Economics Group and conducting my own studies through the EPIC Undergraduate Summer Research Fellowship, I’ll have plenty of places to apply economics to environmental problems.

These opportunities will hopefully also give me the chance to give back to the UChicago community and I’ll try to share my high school experiences of teaching children as a Climate Reality Leader and leading the school energy club’s various experiments and research.

But outside my focus in economics and environmental studies, I hope to take courses like Contemporary French Cinema to deepen my understanding about French culture, as well as Dinosaur Science, a course I’ve been interested ever since I received a UChicago email two years ago.

Though all of this will occupy most of my time, I’m going to try to squeeze in time to play pétanque with the Lawn Sport Enthusiasts as well as visiting the museums around Chicago. With some luck, I’ll find other art history freaks for whom “museum-going” is an exciting weekend plan and together, we’ll become well-acquainted with Mary Cassatt and Robert Delaunay paintings at the Art Institute of Chicago by the end of our four years, not to mention Opo Ogaga.

I’m sure that Chicago will be the best place for me to start my career as an energy economist and researcher. But speaking of research, there’s one thing I was troubled about in my Becker Friedman fantasy. Will Chicago kids settle for Chupa Chups? Or is there some Midwest treat I’ll have to discover?

中文翻譯

我一邊觀察芝加哥高地幼兒(er) 中心的孩子們(men) ,一邊潦草地記錄他們(men) 如何分享我給他們(men) 的有限零食,以及他們(men) 在討論誰得到什麽(me) 時經曆了哪些階段。看完幾個(ge) 小組分配他們(men) 稀缺的資源後,我給每個(ge) 孩子一個(ge) 棒棒糖,然後帶著滿滿的筆記本離開了中心。

幾小時後,我沿著第59街步行前往貝克爾-弗裏德曼研究所。當我放下 "環境項目 "的觀察結果時,我很興(xing) 奮,因為(wei) 通過芝加哥實驗計劃,我將在約翰-利斯特教授等經濟學家的領導下為(wei) 實驗經濟學做出貢獻。

好吧,我想我可能不會(hui) 馬上得到貝克爾-弗裏德曼研究所學生誌願者的職位。但對我來說,這個(ge) 小小的幻想象征著作為(wei) 一名未來的能源經濟學家,我想在芝加哥大學經曆的一切。在芝加哥大學學習(xi) 對我來說是夢想成真:將經濟學帶入日常生活,應用於(yu) 環境問題,同時漫遊芝加哥,享受樂(le) 趣。

在芝加哥大學,就經濟學而言,我期待通過選修《實驗經濟學》和《創造力》等獨特的課程,深入學習(xi) 我的專(zhuan) 業(ye) ,在核心的微觀/宏觀經濟學之外,進一步加深對經濟學的理解。

我相信,作為(wei) 一名能源經濟學家,我的職業(ye) 生涯需要創造性和實驗性思維,而這兩(liang) 門課程將為(wei) 我迎接挑戰做好充分準備。同樣,我也很高興(xing) 能選修《拍賣理論》(Theory of Auctions),這門課程將為(wei) 我進一步研究碳限額交易市場提供必要的知識。

至於(yu) 我對環境的興(xing) 趣,我希望通過環境與(yu) 城市研究輔修課程中的環境經濟學與(yu) 政策方向來探索這一領域,這一選擇非常適合我。從(cong) 以政策製定為(wei) 重點的必修課程開始,我還希望學習(xi) 能源、科學、技術和人類使用等課程:科學、技術與(yu) 人類使用》和《冰川學入門》等課程,以加強我在環境科學方麵的基礎,因為(wei) 我的職業(ye) 生涯需要更多這方麵的專(zhuan) 業(ye) 知識。我還計劃選修《文學、藝術和電影中的氣候變化》(ENST 12520),研究大眾(zhong) 媒體(ti) 如何描述環境問題,以及從(cong) 人文學科的角度看氣候變化是什麽(me) 樣的。

我很高興(xing) 能有機會(hui) 在芝加哥大學將這兩(liang) 個(ge) 感興(xing) 趣的領域結合起來。從(cong) 在氣候和能源政策穩健決(jue) 策中心指導高中生的研究,到與(yu) 綠色經濟小組討論芝加哥大學的可持續發展計劃,再到通過EPIC本科生暑期研究獎學金開展自己的研究,我將有很多機會(hui) 將經濟學應用於(yu) 環境問題。希望這些機會(hui) 也能讓我有機會(hui) 回饋芝加哥大學社區,我會(hui) 努力分享我在高中作為(wei) 氣候現實領導者教導孩子們(men) 以及領導學校能源俱樂(le) 部進行各種實驗和研究的經曆。

除了經濟學和環境研究之外,我還希望選修當代法國電影等課程,以加深我對法國文化的了解,同時我還希望選修恐龍科學這門課程,自從(cong) 兩(liang) 年前收到芝加哥大學的郵件後,我就對這門課程產(chan) 生了濃厚的興(xing) 趣。

雖然這一切將占據我大部分的時間,但我還是會(hui) 盡量擠出時間與(yu) 草坪運動愛好者們(men) 一起打打壁球,順便參觀一下芝加哥附近的博物館。如果運氣好的話,我還能找到其他藝術史狂人,對他們(men) 來說,"參觀博物館 "是一個(ge) 令人興(xing) 奮的周末計劃,到四年結束時,我們(men) 將一起熟悉芝加哥藝術學院的瑪麗(li) -卡薩特(Mary Cassatt)和羅伯特-德勞內(nei) (Robert Delaunay)的畫作,更不用說奧波-緒加(Opo Ogaga)了。

我相信,芝加哥將是我開始能源經濟學家和研究員職業(ye) 生涯的最佳地點。但說到研究,有一件事讓我在貝克爾-弗裏德曼的幻想中煩惱不已。芝加哥的孩子們(men) 會(hui) 滿足於(yu) Chupa Chups 嗎?還是中西部有什麽(me) 美食需要我去發掘?

03、芝加哥大學新生範文

英文原文

The human mind tends to dislike inconsistencies. Possibly for this reason, philosophers created (or discovered?) the “law of non-contradiction”: for example, something can’t be limited and unlimited at the same time. So if there’s a limited amount of matter in the universe (clearly an assumption, but let’s grant it and see where it takes us), how can Olive Garden serve an infinite amount of food (not that I’d complain about more breadsticks)?

Both Eastern and Western philosophy have, perhaps without realizing it, struggled with the Olive Garden dilemma for centuries. One possible answer lies in the condition “at the same time.”

True, matter in the universe might be limited at any single point in time, and so is the amount of food Olive Garden can produce, but Olive Garden is making food ALL THE TIME! Chemistry, biology, and environmental science all teach us that matter and energy recycle, something mirrored in Neo-Confucian cosmology.

In the li- qi (principle-matters) system, the li of the universe is fixed, and the qi at any time is limited, but as time goes on, the qi breaks and reorganizes itself according to the li, destroying and creating matter endlessly.

The Hegelian dialectic, while working a little differently, shows the same thing. The Thesis and the Anti-Thesis are limited at a given point in time, but as their conflicts grow and materialize over time, a Synthesis is formed -- creating stuff endlessly! (Well, maybe until the “end of history.”) The Daoist dichotomy of Yin and Yang goes a step further: “The Supreme Void divides to The Two; the Two give birth to The Four; The Four create The Eight....”

As the two essential elements group and regroup themselves, myriad creatures are being created, disintegrated, and recreated.

The spirit of this self-generative binary paradigm is continued in modern Computer Science, where groupings of 0’s and 1’s generate infinite possibilities. Although the computer has only limited storage, variations with time create limitless images on the screen. Similarly, although the universe has only a limited amount of matter, over an infinitely long period of time Olive Garden can surely serve limitless amounts of food.

Even if the amount of matter in this universe is finite, we have no way of knowing it -- the universe could be bound, but its terminus is beyond our perception. Similarly, the food at Olive Garden could in fact be limited, and the customers might simply perceive it to be limitless because they can’t see its limit. In other words, the food of Olive Garden is made infinite by the customers!

As German philosopher Immanuel Kant formulated in his Critique of Pure Reason, the unperceivable world -- the thing-in-itself, aka the secrets in the kitchen -- is unknowable and could be finite or infinite.

But what makes it seem infinite is our limited capacity to know, or in this case, to eat. I’m sure many creatures of enormous appetite (myself included) have tried to eat an Olive Garden empty, just as those of outstanding intellect have tried to explore the metaphysical reality of the world, but as far as I know, none have succeeded. This makes the food at Olive Garden effectively infinite.

Political theories offer tantalizing possibilities for explanation, until each is devoured in time. The combination of the self-generating matter of the universe and the limited capacity of mind -- parallel to the continuously refilling Olive Garden salad bar and the limited appetite of each of us -- can lead to a feeling of frustration. I remember a time when I almost finished off the salad bar, but seconds later they refilled it.

Nothing could encompass how I felt at that moment besides the word “frustration.” Francis Fukuyama, one of my favourite contemporary political philosophers, likely had the same frustration when he concluded in 1989 that “history has ended with the globalization of liberal democracy,” only to be proven wrong as cultural and ethnic conflicts arose in the 1990s.

Fukuyama’s teacher, Samuel Hungtington, then tried to capture this new political zeitgeist in his “Clash of Civilizations,” only to be proven in-comprehensive when ideological conflicts took place again in the Middle East in the 2000s. Numerous other theories arose to make sense of our geopolitics, and some did a good job -- for a period of time.

As the situation itself keeps changing, those theories inevitably become less accurate and less relevant. Political phenomena in the world, like the food at Olive Garden, just keep presenting themselves ceaselessly, and neither our minds nor our appetites seem capable of fully handling them.

Hence, we start to question the question. Things -- food and the world -- seem so limitless and overwhelming that we start to doubt whether there’s only a limited amount of matter after all. Maybe the initial proposition itself is wrong!

As I wrote this previous line, I finally realized how infinity is truly possible: it is our very ability to doubt, to think outside the box, to question fixed propositions, that is truly infinite. My favourite philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn, acknowledges as much: true, no single account of the world is fully accurate, but in attempting to formulate those accounts, we create many different ways of looking at the world -- many mini-worlds to ourselves. Each “paradigm shift” is a complete revolution of thought, a collective “thinking outside the box,” a fruit of human creativity, which is limitless and leads us closer and closer to the ultimate reality.

I guess that’s why Olive Garden is so popular.

中文翻譯

人的思維往往不喜歡前後矛盾。可能正是出於(yu) 這個(ge) 原因,哲學家們(men) 創造(或發現?)了“不矛盾律”:例如,一件事物不可能同時是有限和無限的。那麽(me) ,如果宇宙中的物質是有限的(這顯然是一個(ge) 假設,但我們(men) 姑且相信它,並看看它能把我們(men) 帶向何方),橄欖園又怎麽(me) 能提供無限量的食物呢(我倒不是抱怨要更多的麵包條)?

幾個(ge) 世紀以來,東(dong) 方哲學和西方哲學也許都在不知不覺中與(yu) 橄欖園的難題作鬥爭(zheng) 。一個(ge) 可能的答案在於(yu) “同時”這個(ge) 條件。誠然,宇宙中的物質在任何一個(ge) 時間點上都可能是有限的,橄欖園所能生產(chan) 的食物數量也是有限的,但橄欖園無時無刻不在生產(chan) 食物!化學、生物學和環境科學都告訴我們(men) ,物質和能量是循環的,這一點在新儒家宇宙觀中也有所體(ti) 現。

在“裏-氣”(原理-物質)係統中,宇宙的“裏”是固定不變的,任何時候的“氣”都是有限的,但隨著時間的推移,“氣”會(hui) 根據“裏”的變化而自我打破和重組,無休止地破壞和創造物質。

黑格爾的辯證法雖然運作方式略有不同,但卻體(ti) 現了同樣的道理。正題和反題在特定的時間點上是有限的,但隨著時間的推移,它們(men) 之間的衝(chong) 突會(hui) 不斷增加並具體(ti) 化,從(cong) 而形成一個(ge) 綜合體(ti) --無休止地創造東(dong) 西(也許直到“曆史的終結”。)!道家的陰陽二分法更進一步:“太極生兩(liang) 儀(yi) ,兩(liang) 儀(yi) 生四象,四象生八卦...”。

隨著這兩(liang) 種基本元素的組合和重組,無數生物被創造、分解和再創造。這種自我生成的二進製範式的精神在現代計算機科學中得到了延續,0和1的組合產(chan) 生了無限的可能性。雖然計算機的存儲(chu) 空間有限,但隨著時間的變化,屏幕上會(hui) 出現無限的圖像。同樣,雖然宇宙中的物質數量有限,但在無限長的時間內(nei) ,橄欖園肯定能提供無限多的食物。

即使宇宙中的物質數量是有限的,我們(men) 也無從(cong) 知曉--宇宙可能是有邊界的,但其終點卻在我們(men) 的感知之外。同樣,橄欖園的食物實際上可能是有限的,而顧客可能隻是因為(wei) 看不到它的極限而認為(wei) 它是無限的。

換句話說,橄欖園的食物因顧客而變得無限!正如德國哲學家伊曼紐爾-康德在《純粹理性批判》中所闡述的,不可感知的世界--事物本身,也就是廚房裏的秘密--是不可知的,可能是有限的,也可能是無限的。

但讓它看起來無限的是我們(men) 有限的認知能力,或者說在這裏,我們(men) 有限的吃的能力。我相信許多食欲旺盛的生物(包括我自己)都曾試圖吃空橄欖園的食物,就像那些智力超群的人試圖探索世界的形而上現實一樣,但據我所知,沒有一個(ge) 人成功過。因此,橄欖園的食物實際上是無限的。

政治理論提供了誘人的解釋可能性,直到每一種可能性都被時間吞噬。宇宙中自我生成的物質與(yu) 思維的有限能力--就像橄欖園沙拉吧不斷添滿的食物與(yu) 我們(men) 每個(ge) 人有限的胃口--的結合會(hui) 讓人產(chan) 生挫敗感。我記得有一次,我幾乎吃完了沙拉吧,但幾秒鍾後他們(men) 又重新裝滿了沙拉。除了“挫敗感”這個(ge) 詞,沒有什麽(me) 能概括我當時的感受了。

弗朗西斯-福山(Francis Fukuyama)是我最喜歡的當代政治哲學家之一,當他在1989年得出“曆史已經隨著自由民主的全球化而終結”的結論時,很可能也有過同樣的挫敗感,但隨著20世紀90年代文化和種族衝(chong) 突的出現,他的結論被證明是錯誤的。福山的老師塞繆爾-亨廷頓(Samuel Hungtington)在他的“文明的衝(chong) 突”中試圖捕捉這一新的政治思潮,但在2000年代中東(dong) 再次發生意識形態衝(chong) 突時,他的理論被證明是不全麵的。

為(wei) 了理解我們(men) 的地緣政治,出現了許多其他理論,其中一些在一段時間內(nei) 做得不錯。隨著局勢本身的不斷變化,這些理論的準確性和相關(guan) 性不可避免地會(hui) 降低。世界上的政治現象就像橄欖園的食物一樣,不斷地呈現在我們(men) 麵前,而我們(men) 的頭腦和胃口似乎都無法完全應付。

因此,我們(men) 開始質疑這個(ge) 問題。事物--食物和世界--似乎是如此無邊無際,讓人應接不暇,以至於(yu) 我們(men) 開始懷疑物質的數量是否有限。也許最初的命題本身就是錯的!

當我寫(xie) 下這一行字時,我終於(yu) 意識到無限是如何真正可能的:正是我們(men) 懷疑、跳出框框思考、質疑固定命題的能力,才是真正的無限。我最喜歡的科學哲學家托馬斯-庫恩(Thomas Kuhn)也承認這一點:的確,沒有任何一種對世界的描述是完全正確的,但在試圖製定這些描述的過程中,我們(men) 創造了許多不同的看待世界的方式--我們(men) 自己的許多迷你世界。每一次“範式轉換”都是一次徹底的思想革命,是一次集體(ti) 的“發散思維”,是人類創造力的結晶,它是無限的,引領我們(men) 越來越接近終極現實。

我想這就是橄欖園如此受歡迎的原因吧。

04、芝加哥大學新生範文

英文原文

After asking the children to gather around a large table at the centre of the room, I announce the challenge. “I’m now going to open this bag of lollipops. Take whatever you’d like!”

In a split second hands are scrambling all over the desk and the children scream in delight and in frustration. In a few seconds, everyone retreats from the table to protect their bounty and I see the plastic bag has exploded. Looking around the room, I see a mixture of smiles and frowns just as I expected. Tough Soomin has quickly grabbed hold of eight; little Jaeyong has none.

“Don’t eat them yet! Yes, Junhyeon, I mean it. Just look around, guys. Is everyone happy?”

Many kids shake their heads passionately. Soomin looks a little sheepish.

“OK. But this is where economics comes in, right? I know you’re tired of me saying this by now, but always remember: economics is all about thinking about what to do with all our stuff.”

Bringing up the PowerPoint slide, I introduce them to the Tragedy of the Commons and tell them that this way of distribution was Option 1: Leave everyone to do whatever they want, the very process that causes a Tragedy. After collecting their lollipops back (a difficult process that involves my begging), I announce Option 2: Government Regulation.

I pass all the lollipops to Minsoo, assigning him the government role. “Your job is to give out these lollipops to all of your friends, based on what you think is the best way.”

I’m sure this will yield a better result, since this is a textbook economic solution. But I’m surprised. What I see is nothing close; I see our own society. Minsoo gives priority to his closest friends, letting them choose flavors and giving them two each. Many others don’t get the flavor they wanted. When he has left-overs, he pockets a few for himself.

My presentation loses a lot of meaning with many kids still unhappy. Afterwards, other solutions like communist systems and auctions with Monopoly money don’t work much better. I’m hoping that the final solution will work though.

Bringing back all the lollipops to the center table, I announce the ultimate solution, promising kids that after this round they’ll be able to keep their lollipops.

“I’m giving you guys ten minutes to talk about who should get what. I want everyone to be happy!”

I watch the debate closely, hoping to see the negotiation process bear fruit as predicted by Nobel laureates Elinor Ostrom and Ronald Coase. This is supposed to be the best solution for small communities, and it appears so. After spending weekends together, the children know each other well enough for discussion.

Those who don’t want lollipops quickly announce their decisions and help monitor the debate. When they eventually work out something, I ask them if they consider this to be the best solution. Everyone seems to nod and I end the lesson after presenting the ideas of Ostrom and Coase.

I pack my stuff after the lesson when two children come to me. “We didn’t get the flavour we wanted. There were some people who secretly took the flavour we wanted and we had to let them because they were older than us.” I tell them to wait, and quickly return with the lollipop flavours they wanted from a nearby convenience store. At least they have a smile as they go back home. But I’m slightly troubled.

I was simulating an economy with some twenty children. But the difficulties of finding a solution even in this microcosm had me thinking: what about the real world?

I’ve learnt that the world is complex and that it’s easy to miss so many important people by relying on classroom theory. It’s why I hope to start tackling the world’s problems at UChicago, to make sure that, as much as possible, everyone gets the lollipops they want. And that’s what lollipops have taught me.

中文翻譯

請孩子們(men) 圍在教室中央的一張大桌子旁,然後我宣布挑戰開始。"現在我要打開這袋棒棒糖。你們(men) 想拿什麽(me) 就拿什麽(me) !"

霎時間,桌子上到處都是爭(zheng) 搶的手,孩子們(men) 高興(xing) 地叫著,沮喪(sang) 地看著。幾秒鍾後,每個(ge) 人都從(cong) 桌子上退了下來,保護自己的 "戰利品",我看到塑料袋已經爆炸了。環顧四周,正如我所預料的那樣,孩子們(men) 笑臉相迎,眉頭緊鎖。堅強的 Soomin 很快就搶到了八個(ge) ,而小 Jaeyong 一個(ge) 也沒有。

"先別吃!是的,俊賢,我是認真的。你們(men) 看看周圍。大家都開心嗎?"

許多孩子熱情地搖頭。蘇敏看起來有點害羞。

"好吧,但這就是經濟學的作用,對嗎?我知道你們(men) 現在已經厭倦了我說這些,但請永遠記住

記住:經濟學就是思考如何處理我們(men) 所有的東(dong) 西。

我拿出 PowerPoint 幻燈片,向他們(men) 介紹 "公地悲劇",並告訴他們(men) 這種分配方式是方案 1:讓每個(ge) 人都為(wei) 所欲為(wei) ,而這正是導致悲劇的過程。在收回他們(men) 的棒棒糖後(這是一個(ge) 艱難的過程,需要我的乞求),我宣布了方案 2:政府監管。

我把所有的棒棒糖都遞給了民秀 讓他扮演政府的角色 "你的任務就是把這些棒棒糖分給你所有的朋友" "根據你認為(wei) 最好的方法"。

我相信這會(hui) 產(chan) 生更好的結果,因為(wei) 這是一個(ge) 教科書(shu) 式的經濟解決(jue) 方案。但我很驚訝。我看到的並不接近,我看到的是我們(men) 自己的社會(hui) 。Minsoo 優(you) 先考慮他最親(qin) 密的朋友,讓他們(men) 選擇口味,每人給他們(men) 兩(liang) 個(ge) 。很多其他人都沒有得到他們(men) 想要的口味。當他吃剩的時候,會(hui) 給自己留一些。

我的演講失去了很多意義(yi) ,很多孩子還是不開心。之後,其他的解決(jue) 方案,比如共產(chan) 主義(yi) 製度和用大富翁的錢進行拍賣,效果都不怎麽(me) 好。不過,我希望最終的解決(jue) 方案能夠奏效。

我把所有的棒棒糖拿回到中間的桌子上,宣布了最終解決(jue) 方案,並向孩子們(men) 承諾,這一輪之後,他們(men) 就可以保留自己的棒棒糖了。

"我給你們(men) 十分鍾時間討論誰應該得到什麽(me) 。我希望大家都開心!"

我密切關(guan) 注這場辯論,希望看到談判進程如諾貝爾獎獲得者埃莉諾-奧斯特羅姆和羅納德-科斯所預言的那樣取得成果。對於(yu) 小社區來說,這應該是最好的解決(jue) 方案,看起來也是如此。

在一起度過周末後,孩子們(men) 彼此熟悉,足以進行討論。那些不想要棒棒糖的孩子很快就會(hui) 宣布他們(men) 的決(jue) 定,並幫助監督辯論。當他們(men) 最終達成一致時,我問他們(men) 是否認為(wei) 這是最好的解決(jue) 方案。大家似乎都點了點頭,在介紹了奧斯特羅姆和科斯的觀點後,我結束了這節課。

下課後,我收拾東(dong) 西時,兩(liang) 個(ge) 孩子走了過來。"我們(men) 沒有得到想要的味道。有一些人偷偷拿走了我們(men) 想要的味道,我們(men) 不得不讓他們(men) 拿走,因為(wei) 他們(men) 比我們(men) 大。我讓他們(men) 等一下,然後迅速從(cong) 附近的便利店買(mai) 了他們(men) 想要的口味的棒棒糖回來。至少,他們(men) 在回家的路上還帶著微笑。但我還是略感煩惱。

我是在模擬一個(ge) 有二十來個(ge) 孩子的經濟體(ti) 。但即使在這個(ge) 微觀世界中也很難找到解決(jue) 方案,這讓我想到:現實世界又如何呢?

我了解到,世界是複雜的,依靠課堂理論很容易錯過許多重要的人。這就是為(wei) 什麽(me) 我希望在芝加哥大學開始解決(jue) 世界問題,盡可能確保每個(ge) 人都能得到他們(men) 想要的棒棒糖。這就是棒棒糖教會(hui) 我的。

05、芝加哥大學新生範文

英文原文

I could always tell when summer started by the number of mosquito bites I had on my leg. And as an 8 year old--exasperated by endless Band-Aids and cortisone globs--the mosquitoes’ constant nagging bothered me.

Was my blood too sweet? Did I fight too much with my brother? Only through the Internet did the diagnosis become clear: light clothing and constant motion were homing targets for the parasites. More research revealed that the bites swelled so much because of a histamine response the body sent to fight the anticoagulant the mosquito carried.

But these questions only led to more questions – not just about my bites, but about the people around me. Why did Grandma prick her finger every day and count rice grains? Why was Grandpa not able to speak? Biology answered all of them.

From the fibrin nets that make up my scabs to the millions of scattered wavelengths that create the earthy hue of my mom’s spider plants, biology was my portal to understanding life and its endless kaleidoscope of mysteries. It translated the foreignness of toothaches, goosebumps, and common colds into a language that the little me could speak. It served as my own map to the world’s hidden trove of secrets and became a sense of wonder and comfort I could rely on.

But as I got older biology gave me an insatiable desire to go beyond hole punching leaf disks to measure photosynthesis. I took it upon myself to explore a different kind of animal than mosquitoes: the human mind.

This past summer, I assisted Dr. Mark Fisher at UC-Irvine with his research about cerebral micro-bleeds in young athletes. I recruited local high school students, whose MRI scans and medical histories were studied to make earlier and more effective diagnoses of CTE, a degenerative disease brought on by repeated concussions. I also attended medical journal club meetings with prospective medical students each Friday, where I learned about the risks of tPA treatment in ischemic stroke patients, the use of optical histology, and other facets of neurology.

But biology is not only a portal to comprehending the world around me. It has also become a gateway to understanding myself. Learning that the immune system uses the antigen of invaders to fortify its own defences taught me to persevere when my results fall short of my expectations and embrace my vulnerabilities to my advantage.

Learning that humans share 99% of the same DNA can teach me to appreciate humanity's similarities instead of being divided by its differences.

But most of all, learning that the body can learn to walk again, even after paralysis, taught me to have hope in the face of disease and disaster--to maintain faith in the human spirit and see life as Asagai did in a Raisin in the Sun: not an endless circle we futilely march around and around in but a line of infinite possibility.

Just as Alice found her identity after falling down the rabbit hole, as Milo found a love for life and learning through the phantom tollbooth, and Neo saw truth and reality by taking the red pill, I discovered in biology the paradox of living.

Through the erosion of telomerase sequences and apoptosis of cells, biology showed me how incredibly mortal we are as human beings. But despite our corporeal limitations, biology showed me that we can achieve immortality. We can rise above our earthly circumstances and allow our minds to transcend and our hearts to conquer atrophy and illness.

We empower our bodies to recover by simply believing in the effect of a placebo. We reduce our coronary heart risk and prolong our lifespans by reducing stress and thinking optimistically.

Through the power of the mind, our bodies can heal.

Through the faculty of thoughts, we hold the mantle to shape our own fates.

And through the portal of biology, I find time and time again vitality, strength, and autonomy.

中文翻譯

我總是能從(cong) 腿上被蚊子叮咬的次數判斷出夏天是什麽(me) 時候開始的。作為(wei) 一個(ge) 8 歲的孩子,我對無休止的創可貼和可的鬆感到厭煩,蚊子不斷的嘮叨讓我心煩意亂(luan) 。

我的血是不是太甜了?我是不是和哥哥打得太多了?隻有通過互聯網,診斷才變得清晰起來:輕薄的衣服和持續的運動是寄生蟲的歸宿目標。更多的研究表明,被叮咬的地方之所以會(hui) 腫脹,是因為(wei) 身體(ti) 為(wei) 了對抗蚊子攜帶的抗凝血劑而產(chan) 生的組胺反應。

但這些問題隻會(hui) 引出更多的問題--不僅(jin) 是關(guan) 於(yu) 我的叮咬,還有關(guan) 於(yu) 我周圍的人。為(wei) 什麽(me) 奶奶每天都要紮手指數米粒?為(wei) 什麽(me) 爺爺不能說話?生物學回答了所有這些問題。

從(cong) 構成我痂皮的纖維蛋白網,到創造我媽媽蜘蛛植物泥土色澤的數百萬(wan) 個(ge) 散射波長,生物學是我理解生命及其無盡的萬(wan) 花筒奧秘的入口。它將牙痛、雞皮疙瘩和普通感冒的陌生感轉化成了小小的我所能使用的語言。它是我通往世界秘密寶庫的地圖,成為(wei) 我可以依賴的驚奇和安慰。

但隨著年齡的增長,生物學給了我永不滿足的欲望,讓我不再局限於(yu) 在葉片上打孔來測量光合作用。我開始探索一種與(yu) 蚊子不同的動物:人類的大腦。

去年夏天,我協助加州大學爾灣分校的馬克-費舍爾博士研究年輕運動員的腦微小出血。我招募了當地的高中生,對他們(men) 的核磁共振掃描和病史進行研究,以便更早、更有效地診斷出 CTE(一種由反複腦震蕩引起的退行性疾病)。我還參加了每周五與(yu) 未來醫科學生舉(ju) 行的醫學期刊俱樂(le) 部會(hui) 議,了解了缺血性中風患者接受 tPA 治療的風險、光學組織學的應用以及神經病學的其他方麵。

但生物學不僅(jin) 是我理解周圍世界的入口。它也是了解我自己的門戶。當我了解到免疫係統會(hui) 利用入侵者的抗原來加強自身的防禦能力時,我學會(hui) 了在結果不盡如人意時堅持不懈,並將自己的弱點轉化為(wei) 優(you) 勢。

了解到人類擁有 99% 相同的 DNA,可以讓我學會(hui) 欣賞人類的相似之處,而不是被其差異所分裂。但最重要的是,了解到身體(ti) 即使在癱瘓後也能學會(hui) 重新行走,讓我學會(hui) 了在疾病和災難麵前抱有希望--保持對人類精神的信心,並像《陽光下的葡萄幹》中的朝日一樣看待生命:這不是一個(ge) 我們(men) 徒勞地繞來繞去的無盡圓圈,而是一條充滿無限可能的線。

正如愛麗(li) 絲(si) 掉進兔子洞後找到了自己的身份,米洛通過幽靈收費站找到了對生活和學習(xi) 的熱愛,尼奧通過服用紅色藥丸看到了真理和現實,我在生物學中發現了生命的悖論。通過端粒酶序列的侵蝕和細胞的凋亡,生物學向我展示了作為(wei) 人類,我們(men) 是多麽(me) 令人難以置信的凡人。但是,盡管我們(men) 的肉體(ti) 受到限製,生物學卻告訴我,我們(men) 可以實現永生。我們(men) 可以超越世俗的環境,讓我們(men) 的思想超越,讓我們(men) 的心靈戰勝萎縮和疾病。我們(men) 隻需相信安慰劑的效果,就能讓身體(ti) 恢複健康。通過減輕壓力和樂(le) 觀思考,我們(men) 可以降低冠心病風險,延長壽命。

通過思想的力量,我們(men) 的身體(ti) 可以痊愈。

通過思想的力量,我們(men) 可以掌握自己的命運。

通過生物學的門戶,我一次又一次地發現了活力、力量和自主性。

由於(yu) 篇幅限製,本文先跟大家分享5篇芝加哥大學的優(you) 秀範文。

評論已經被關(guan) 閉。